www.

nchra

.org

13

why we can’t multitask. That’s why people find

themselves losing track of previous progress and

needing to “start over,” perhaps muttering things

like “Now where was I?” each time they switch

tasks. The best you can say is that people who

appear to be good at multitasking actually have

good working memories, capable of paying

attention to several inputs one at a time.

Here’s why this matters: Studies show that a

person who is interrupted takes 50 percent longer

to accomplish a task. Not only that, he or she

makes up to 50 percent more errors.

A good example is driving while talking on a

cell phone. Until researchers started measuring

the effects of cell-phone distractions under

controlled conditions, nobody had any idea how

profoundly they can impair a driver. It’s like driving

drunk. Recall that large fractions of a second are

consumed every time the brain switches tasks.

Cell-phone talkers are a half-second slower to

hit the brakes in emergencies, slower to return

to normal speed after an emergency, and more

wild in their “following distance” behind the vehicle

in front of them. In a half-second, a driver going

70 mph travels 51 feet. Given that 80 percent

of crashes happen within three seconds of

some kind of driver distraction, increasing your

amount of task-switching increases your risk of an

accident. More than 50 percent of the visual cues

spotted by attentive drivers are missed by cell-

phone talkers. Not surprisingly, they get in more

wrecks than anyone except very drunk drivers.

It isn’t just talking on a cell phone. It’s putting on

makeup, eating, rubber-necking at an accident.

One study showed that simply reaching for an

object while driving a car multiplies the risk of a

crash or near-crash by nine times. Given what we

know about the attention capacity of the human

brain, these data are not surprising.

Do one thing at a time

The brain is a sequential processor, unable to

pay attention to two things at the same time.

Businesses and schools praise multitasking,

but research clearly shows that it reduces

productivity and increases mistakes. Try creating

an interruption-free zone during the day—turn off

your e-mail, phone, IM program, or BlackBerry—

and see whether you get more done.

HR

Excerpt from Brain Rules.

Reprinted with permission.

Dr. John Medina, a developmental

molecular biologist, has a

lifelong fascination with how the

mind reacts to and organizes

information. He is the author of

the New York Times bestseller

"Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at

Work, Home, and School" — a provocative book that

takes on the way our schools and work environments are

designed. His latest book is a must-read for parents and

early-childhood educators: "Brain Rules for Baby: How to

Raise a Smart and Happy Child from Zero to Five." Medina

is an affiliate Professor of Bioengineering at the University

of Washington School of Medicine. He lives in Seattle,

Washington, with his wife and two boys.

Multitasking Myth

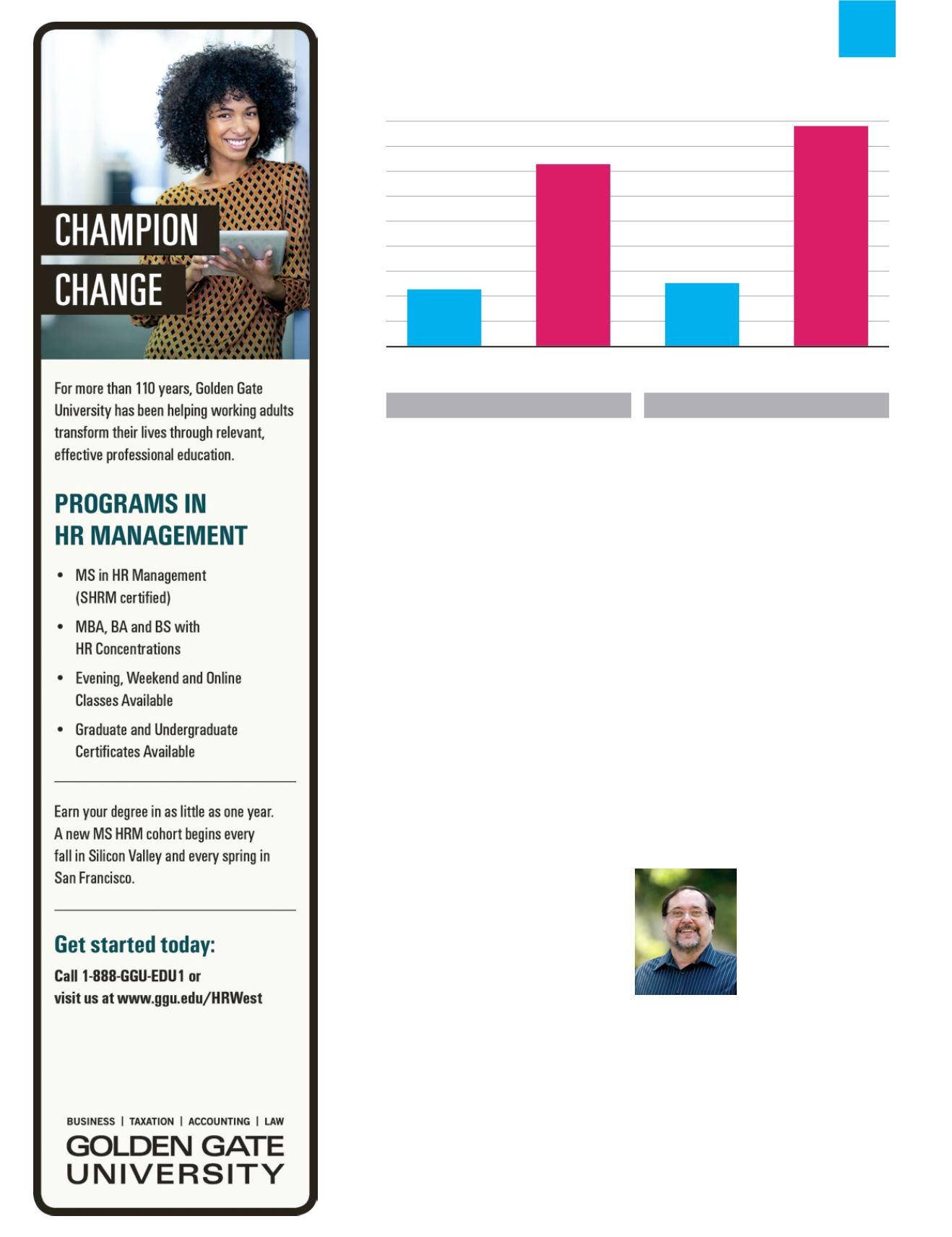

Source:

Rogers RD & Monsell,S (1995) Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory Journal of Experimental Psychology:General 124(2):207 - 231

Table 2 of Experiment Cluster #1 (crosstalk conditions).

Notes:

These trials involved uninterrupted (single-focus) tasks and interrupted (multiple-focus) tasks.Data are shown

for experiments involving number-based manipulations and letter-based manipulations. Some people, particularly younger people, are more adept at task-switching. If a

person is familiarwith the tasks,thecompletion timeanderrorsaremuch less than if the tasksareunfamiliar.Still,takingyoursequentialbrain intoamultitaskingenvironment

can be like trying to put your right foot into your left shoe.

0

2

4

6

8

Percent Error

NOT switching

NOT switch-

ing

NOT switching

NOT

switching NOT switching

NOT

switching

NOT switch-

ing

NOT

switching NOT

switching

switching switching

switching

NOT

switching

switching switching

switching

switching

NOT switching

NOT

switching

NOT switching

NOT switch-

ing

NOT switching

NOT

switching NOT switching

NOT

switching

NOT switch-

ing

NOT

switching NOT

switching

switching switching

switching

NOT

switching

switching switching

switching

switching

NOT switching

NOT

switching

switching

switching

switching

switching switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching switching

switching switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching switching

switching switching

switching

switching

switching

switching switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching switching

switching switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching

switching

switch-

ing

switching

switching

switching switching

switching switching

Error Percentages for No-Switching and Switching Activities

Tasks involved

numerical

manipulations

No switching

between tasks

No switching

between tasks

Switching

between tasks

Switching

between tasks

Tasks involved

letter

manipulations