28

Vol. 66, No. 3 2015

Northeast Florida Medicine

Endovascular Neurosurgery

Unruptured Aneurysms

The large majority of asymptomatic unruptured aneurysms

arediscovered incidentally, onbrainCTorMRI studies ordered

by referring physicians. Symptomatic unruptured aneurysms

may cause symptoms from mass effect and compression of

adjacent neurovascular structures, inflammation related to

aneurysm thrombosis or rapid aneurysm expansion. Symp-

tomatic aneurysms have worse natural history compared to

asymptomatic lesions and thus warrant prompt treatment.

Acutelysymptomaticaneurysmsshouldprompttheworkupfor

SAH, sudden increase in aneurysm size or less frequently, acute

aneurysm thrombosis. The prototypical scenario is a posterior

communicating aneurysm that produces the subacute onset

of a third cranial nerve palsy, warranting accelerated imaging

and treatment.

Asymptomatic aneurysms frequently place the treating

physician in a clinical dilemma, because the benefit of treat-

ment must be superior to the natural history. Also, the benefit

of intervening upon asymptomatic lesions is not nearly as

demonstrable as it is in symptomatic or ruptured aneurysms.

Management decisions are rarely straightforward.

There are currently no strict guidelines. The decision

making process is based on unbiased assessment of patient

history and lesion characteristics, and available data regarding

all treatment modalities. Observational cohort studies of

unruptured aneurysms have identified several factors that can

alter the rate of aneurysm formation and rupture.

4-8

These

include: family history of SAH, cigarette smoking, presence of

symptoms attributable to the lesion, irregular shape, narrow

aneurysm neck, size relationship between aneurysm/parent

vessel, aneurysm location, and most prominently, aneurysm

size 4-8 (Tables 1 and 2). Aneurysm size is the single strongest

predictor of aneurysm rupture, yet it should never be used as

the sole indicator. Generally, a 7 mm aneurysm diameter is the

best cut-off point for an increased risk of hemorrhage (Table

3). ISAT investigators found that the mean size of ruptured

lesions was around 5 mm, showing a potential role for treating

smaller unruptured lesions1. Aneurysm location is also an

important factor to consider. For example, lesions located in

the posterior circulation (vertebral artery, basilar artery, and

posterior inferior cerebellar artery), posterior communicating

artery and, more recently, anterior communicating artery have

increased risk of rupture.4,8 In contrast, aneurysms located in

the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery havemuch

lower riskof ruptureunless symptomaticor larger than13mm.8

Exercise cautionwhendealingwith so-called cavernous lesions.

Transition aneurysms (lesions past the “distal dural ring” and

located in the subarachnoid space) may be mistakenly labeled

as cavernous aneurysms.Transitionaneurysms behave clinically

as non-cavernous lesions and must be dealt with as such.

Cigarettesmokinghasbeenassociatedwithahigherlikelihood

of developing intracranial aneurysms, accelerated aneurysm

growth and increased risk of rupture.

4,9

First-degree relatives

of patients with aneurysms also have an increased risk of

harboring an incidental lesion. Individuals with one first-de-

gree relative affected have an increased risk of 4 percent

to 5.6 percent compared to the general population. That

risk doubles to approximately 8 percent if two first-degree

relatives are affected.

8

Therefore, screening for incidental

lesions is recommended in these circumstances, especially

Figure 2:

Detachable embolization coils are used to fill the

aneurysm sac and create stagnation of blood flow, leading to aneurysm

occlusion. Today, these coils are developed to produce 3-dimensional

shapes before being detached inside the aneurysm sac to optimize

filling of the lesion and improve the rates of aneurysm occlusion.

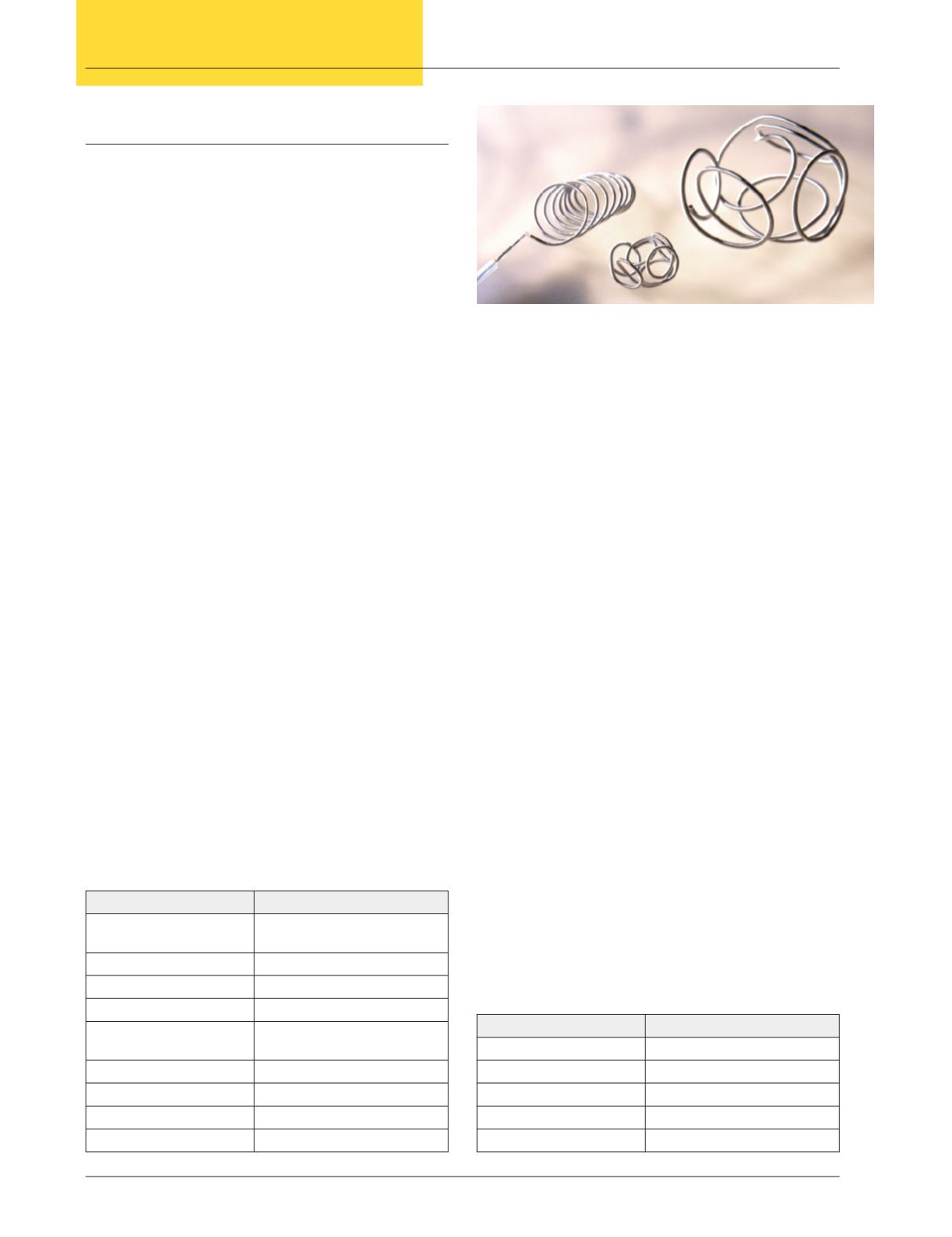

Table 1.

Risk Factors to Develop Intracranial Aneurysms

General risk factors

Inherited risk factors

Female gender

Autosomal dominant polycystic

kidney disease

Cigarette smoking

Fibromuscular dysplasia

Hypertension

Type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Age over 50 years

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

First-degree relative with

aneurysm

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangi-

ectasia

Cocaine use

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Infection of vessel wall

Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neoplastic emboli

Pheochromocytoma

-

Tuberous sclerosis

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Aneurysm Rupture

Patient-related

Aneurysm-related

Cigarette smoking

Aneurysm size

Previous SAH

Aneurysm location

-

Irregular shape (daughter sac)

-

Narrow neck

-

Parent vessel/aneurysm relation